A few months ago, I saw a video on TikTok of a young white woman showing off her outfit, spinning and posing, demonstrating to her audience of other young women how good an Alo yoga set looks on her thin body. I jerked open the comments before my subconscious could register her thigh gap (too late).

The comment section was populated with the usual suspects: “omg where did you get the set?” “where is the necklace from??” “what’s your workout routine?!” “why isn’t she telling us where she got the set???” Always a frenzy of wanting, of willingness to purchase. I scrolled until I saw a comment that took my breath away: “I keep pretending I want a BBL body but really this is the body I want.”

I keep pretending I want a BBL body but really this is the body I want.

The perfect body is a product of history. To misquote and perhaps misinterpret Derrida (I do that a lot), it’s a history of differences.1 Aesthetics operate as a sign system, which means something like body size can be imbued with undue significance, and that significance can change over time.

I want to trace a few shifts in how “the perfect body” has been defined, using Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia by Sabrina Strings and the art historical record as my guides. Strings argues that American pro-thinness and anti-fatness stem from the Renaissance and Reformation, when the transatlantic slave trade, religious movements and eugenicist discourses caused the bodies of black and white women to be measured against each other.2

Let’s start at the Renaissance. During the 15th-17th centuries in Italy, France and the Low Countries (which, according to Google, correspond to modern-day Belgium, the Netherlands and French Flanders), white male artists were taking up the project of defining feminine beauty. They wrote their treatises and had their discourses and drew their diagrams, aiming to describe in “scientific” terms what makes a woman’s body good-looking.

Ancient Greek and Roman culture was all the rage during the Renaissance—Roman antiquities were being unearthed in Italy during this time—so it was common for artists to reference classical female nudes such as the Venus de’ Medici. Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus is perhaps the most well-known example of an early Renaissance Venus Pudica (or “modest Venus”—she covers her groin and usually one breast with her hands). This painting was made around 1480, so you can still see some evidence of the Middle Ages styling of the body blending with the classical styling, which favored anatomical correctness and balance.

Johan Zoffany’s Tribuna of the Uffizi was made in the 18th century, so a bit after the Renaissance, but I think it perfectly illustrates the chokehold antiquities had/have on the western painting tradition. This painting portrays the Tribuna room in the Uffizi gallery in Florence, littered with antiquities and the most famous paintings in the collection.3 The Venus de’ Medici stands at the far right, surrounded by men appraising her naked body.

At the bottom center-ish is Venus of Urbino by the Italian Renaissance painter Titian, which was painted around 1534. Titian’s references to the ancient Venus are clear, from the bodily proportions to the modest (or masterbatory, depending which art historian you ask) left hand. Notice how the old Venus and the new turn their faces away from each other, perhaps embarrassed by the orgy taking place around them.

Around the same time Titian was painting his reclining Venus, and ~men of culture~ were having high-minded conversations about the monumental body in scenes much like the one above, the transatlantic slave trade was bringing African people to Europe against their will.

Due to the growing population of black slaves and domestic servants in Europe, the 16th century saw images of black women enter the art historical record. Strings argues that, for a time, black women were rendered in drawings and paintings with the same classically beautiful bodies as white women—their differences were inscribed elsewhere.

Strings points to the “first African Venus” sculpture as a solid (but complicated) example of a black woman rendered with the same references to the classical Venus as white women were during the Renaissance. Stings notes that the woman’s body is proportionate and fleshy like any other Venus, but her blackness is marked by facial features that are “paradigmatically African” and curly hair that is “covered by a nondecorative headdress, a detail unique to African Venus statues.”

The body of the African Venus, Strings argues, “fits within the prevailing idiom of beauty, representing the ‘refined tastes of the ruling elite of Europe’ circulating during the Renaissance.” But, this Venus is seemingly immodest, lacking the shame that causes the Venus Pudica to cover herself with her hands. Strings writes that the cloth rag she carries may signify that she is a domestic servant, adding to the evidence suggesting she is a “profane” or lowly Venus who contrasts the lofty Venus Pudica.

By the 17th century, Stings argues, the “novelty” of black women wore off in areas where the slave trade had been going on the longest. Intrigue gave way to racial defensiveness, and aesthetic preferences shifted to essentialize inferiority in the bodies of black women. No longer equal in bodily allure but separated by social status, “black women were increasingly deemed little, low, and foul,” while voluptuousness “became more and more frequently associated with white women.”

The above two paintings by Peter Paul Rubens, Venus and Bathsheba, differ greatly from the way the African Venus represents a black woman. The African Venus stood alone on her own pedestal, but in these paintings, black women exist as a mere foil for white women’s beauty. Their small frames and short, coiled hair contrast the white women’s bodily abundance and flowing hair. Stings argues that such visual cues communicate “not just difference but destitution, a sense of something wanting.”

The artistic choices made by Rubens and his contemporaries worked to stabilize the social hierarchy by making it seem impossible for black women to be equal to white women in beauty—and not just beauty, but stature and health (plump bodies were considered beautiful in part because they indicated a robust constitution). Based on the state of present-day fatphobia, we already know that white men will dehumanize anything they don’t find sexually attractive, especially when an argument can be made about health.

The next shift—this one is more of a sea change than a shift—takes place during the 18th and 19th centuries. Strings writes that in this period, body size became a sign of national identity in “the context of religious health reform movements and the massive immigration of Irish racial Others.”

While the Renaissance was inspiring a lot of sexy art in southern Europe, the Reformation was giving birth to unsexy Protestantism in northern Europe and then America. For centuries, feminine voluptuousness was considered heavenly, but to the American Puritans, “corpulence” signified sloth, greed, gluttony, ill health and even stupidity. (Etymologically, “voluptuous” comes from the Latin voluptas, meaning “pleasure, delight, enjoyment, satisfaction,” while “corpulent” comes from the Latin corpus, “body” [living or dead] and -ulentus, “full of.”4 5) It’s body love versus body loathing.

Religious reformers decried the pollution of the Americans body politic with too much alcohol and too much rich food. These OG wellness influencers pedaled strict diets to purify the body, and by extension purify the nation and ensure its longevity. (We still call rich foods “decadent,” the word literally meaning “in a state of decline or decay.”6)

And wherever there’s talk of purity, eugenics can’t be far away. These religious reformers felt their national identity was also under threat by various racial Others, including the Irish, so new eugenicist discourses emerged that claimed Irish white people are inferior to Nordic white people because they have blackness in their gene pool. Additionally, by this time, written accounts of European colonizers and merchants “discovering” African people groups had become very popular in America. Moral backwardness was projected onto these people’s bodies through descriptions of insatiable appetites that caused protrusions of excess fat.

Even though white people could literally just look around and see black people with bodies similar to their own in America, these racist accounts retrenched the idea that nonwhite people were visibly uncivilized and inferior by nature. By the end of the 18th century, “it was becoming part of the general zeitgeist that fatness was related to blackness,” Strings writes, with fatness being “treated as evidence of barbarism.”

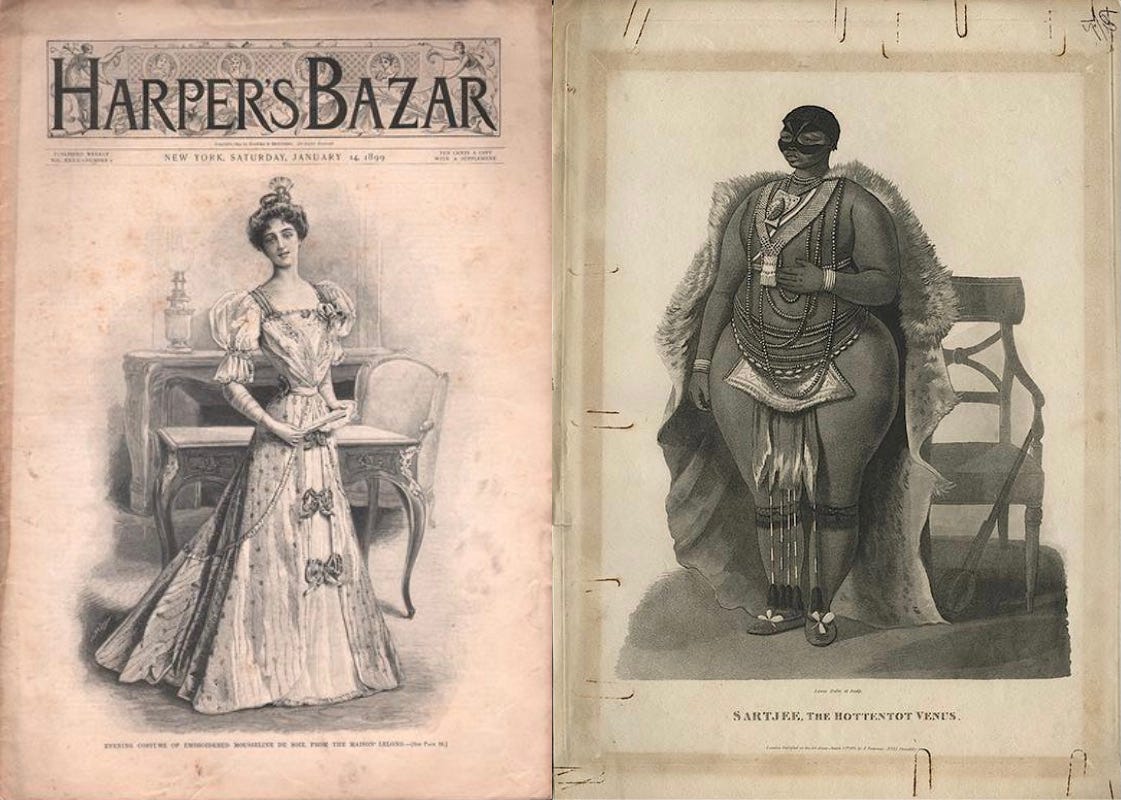

This is the landscape that turned Saartjie Baartman into the “Hottentot Venus.” Hottentot was the name Dutch colonists gave the Khoikhoi people of South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope in the 17th century. Born in the 1770s or 1780s, Baartman was raised on the farm of a colonizer, David Fourie, who took possession of the area where her family had lived, stealing land, property and people, murdering many. Baartman was purchased by a man named Hendrik after her parents died and, due to the size and shape of her buttocks, was taken to England to be displayed as “an erotic and scientific curiosity” in 1810.

On the earliest posters advertising her exhibition, Baartman was called the “most correct and perfect Specimen of that race of people” and was named the Hottentot Venus because she had the “kind of shape which is most admired among her countrymen.” The size of Baartman’s body seemed to fit into the fictions about African people circulating at the time: “…indulging to excess in the gratification of every sensual appetite, the African peasant grows to an unwieldy size,” the 1804 Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa claimed. By other accounts, so-called Hottentot women were tall and slender, but the truth is no match for confirmation bias.

Since thinness was a sign of moral and racial purity and fatness the opposite, white people were primed to see Baartman’s bodily “excess” as proof of African primitivity. Baartman became a symbol of black femininity, and her exhibition helped “make fatness an intrinsically black, and implicitly off-putting, form of feminine embodiment,” Strings argues.

A lot has changed in American culture since the 1800s, of course, but much too much has stayed the same. The “fat black woman” image is still used to denigrate black women and discipline white women. The dominant culture still sees body fat as proof of laziness and indulgence, even immorality. The dominant culture is still titillated and aroused by the bodies it calls immoral. We still use body size as a gauge for health. We still define beauty via difference.

Strings references Derrida’s concept of différance very briefly, almost in passing, but I think it’s a perfect theory to layer over the historical analysis she presents.

Jacques Derrida was an Algerian-French philosopher and post-structuralist. The French verb différer means both “to differ” and “to defer,” and Derrida introduces a reification of this dual meaning by changing the spelling of différence to différance. The two spellings are pronounced the same, so the difference is only discernible in writing. This challenges the notion that meaning is present in speech but deferred in writing, writing being understood as a mere representation of speech.

The neologism illustrates that the presence of meaning is always deferred, it can never be pinned down to one spot, either temporally or spatially. Basically, meaning was never original, is never purely itself, and will never be new. Derrida writes that “we shall designate by the term différance the movement by which language, or any code, any system of reference in general, becomes ‘historically’ constituted as a fabric of differences.”

What is beauty if not a code, and what is art history if not a system of aesthetic reference? I think understanding that “the perfect body” is a fabric of differences generated by an extremely violent history can discourage us from being so… committed to it. (I keep pretending I want a BBL body but really this is the body I want.)

Derrida, Jacques. Différance. Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1968. http://mforbes.sites.gettysburg.edu/cims226/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Week-5a-Jacques-Derrida.pdf

Strings, Sabrina. Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia. New York: NYU Press, 2019.

On Wikipedia you can hover over the artworks in the image to identify them and it’s super fun: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tribuna_of_the_Uffizi_(Zoffany)

“Voluptuous (Adj.).” Online Etymology Dictionary. Accessed July 11, 2022. https://www.etymonline.com/word/voluptuous#etymonline_v_7880.

“Corpulent (Adj.).” Online Etymology Dictionary. Accessed July 11, 2022. https://www.etymonline.com/word/corpulent#etymonline_v_19101.

“Decadent (Adj.).” Online Etymology Dictionary. Accessed July 11, 2022. https://www.etymonline.com/word/decadent#etymonline_v_29316.

"but the truth is no match for confirmation bias." It is ever thus...