The word “acute” sounds like someone pinching their face up. When I hear the phrase “acutely aware” I imagine squinted eyes and pursed lips, some kind of accusation on the tongue. The word “chronic” sounds like creaking, old floorboards or stiff joints. It sounds slow, hollow but with jagged edges.

The Proto-Indo-European root ak- means “be sharp, rise (out) to a point, pierce.”1 An acute illness comes on fast and severe and threatens to get worse quickly. The root chrono- comes from the Greek khronos, time.2 A chronic illness is assumed to hold still at a mild-to-moderate intensity for a long period of time, possibly a lifetime.

Acute illness tends to be visible: it is evident in vital signs and fluid tests if not on the body itself. It’s counterintuitive that something slow-moving would be hard to see, but chronic illness is often invisible to health care structures. Acutely ill people are rushed into hospital beds while chronically ill people sit in primary care waiting rooms, on waitlists to see specialists, sometimes waiting years for a diagnosis.

A pandemic that explodes around the world and immediately starts overwhelming ICUs is an acute crisis. Then two years pass. These days you can go a few hours without hearing or seeing anything about it. You may forget about it entirely for a bit, and then feel a pang of guilt when you realize you had forgotten.

COVID-19 is now a chronic crisis, though chronic crisis sounds like an oxymoron. There are many ways in which COVID-19 is metastasizing as the years pass, exacerbating long-existing problems in school systems, health systems, supply chains, social programs, and so on. I want to focus on long covid, the chronic aftermath of an acute disease. A syndrome that didn’t exist three years ago but will, perhaps, exist forever.

Long covid occurs in about 10% of people who get sick, but some researchers say that number is closer to 30%.3 The CDC says about 1 in 5 Americans who had COVID-19 have long-term symptoms.4 According to data from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91.5 million people in the U.S. have survived COVID-19, which means the number of people experiencing post-acute sequelae (long covid) is likely between 10 million and 27 million.5

Despite the number of people experiencing long covid, diagnostic criteria are still vague. The World Health Organization says symptoms must last “for at least two months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis” to fit the criteria for long covid.6 This process-of-elimination diagnostic method is how doctors try to locate an invisible disease―a very expensive and not-fun game of battle ship.

Treatment guidelines for long covid are also vague and incomplete because the syndrome presents differently in every patient. The CDC and WHO include fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive dysfunction, brain fog, pain, depression, anxiety, cough, headache, digestive issues, and sleep disturbances among possible symptoms.

Due to the nature of long covid, another barrier to care that many patients face is doubt. Doctors tend to dismiss patients who present with invisible symptoms (fatigue, depression, etc., are hard to quantify beyond the word of the patient), and it’s certainly no coincidence that many illnesses characterized by such symptoms are more prevalent among women.

Studies have shown that men are more likely than women to test positive for COVID-19, and among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, men are more likely to have complications, require ICU admission and mechanical ventilation, and die from the disease.7 Given these odds, one might assume men would be more likely to suffer from long covid, but one would be wrong.

Many studies on long covid fail to report sex-disaggregated data, but according to a literature review published in Current Medical Research and Opinion, those that do show that the likelihood of having long covid is significantly greater among female versus male patients.8

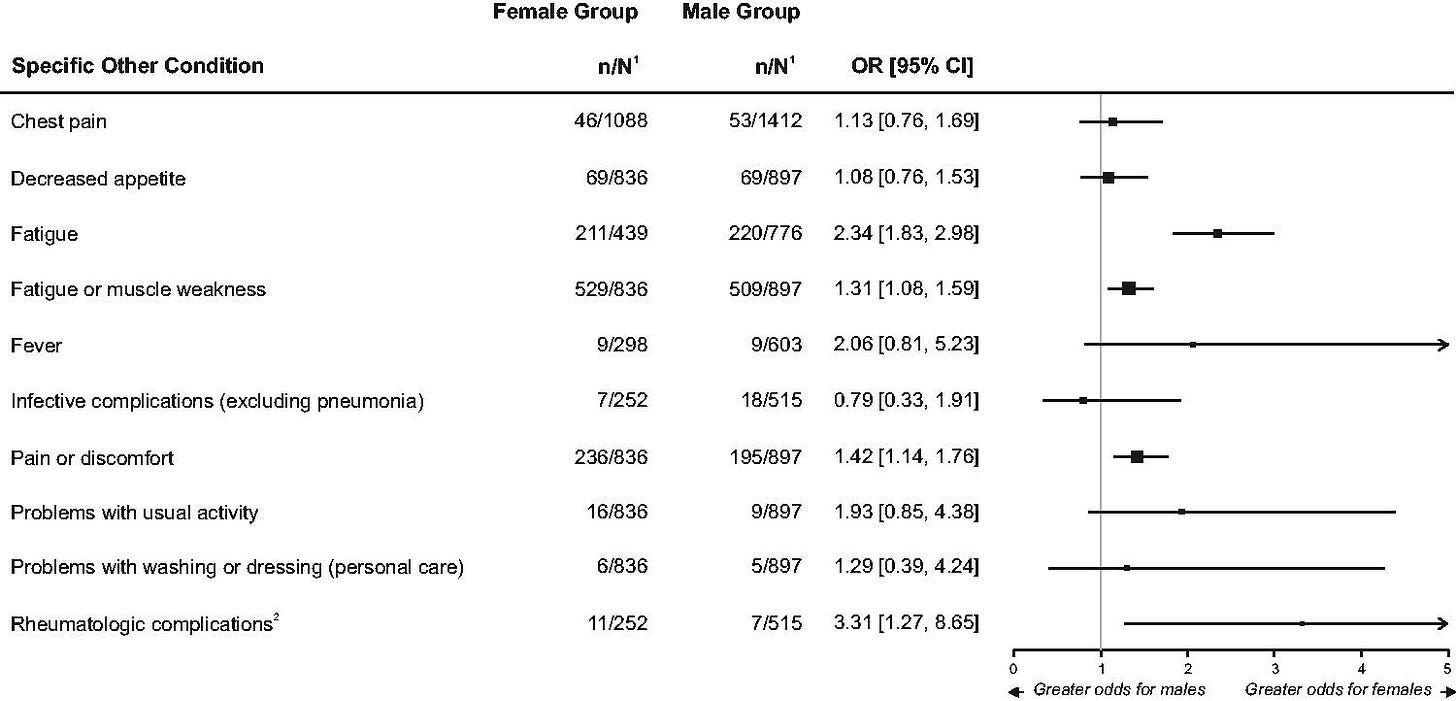

Among the clinical categories implicated in long covid, the review found that ear nose and throat, psychiatric and mood, neurological, dermatological, and “other” disorders were significantly more likely among female long covid patients. The “other” group includes the conditions in the table below.

Being uncategorized means these conditions are harder to manage in a medical sense (for dermatological issues you can go to a dermatologist, but who do you go to for fatigue?). Notice that fatigue, fever, rheumatologic complications and “problems with usual activity” are much more likely (OR = odds ratio) to occur in female versus male patients.

Given these data on the prevalence of long covid among women, and the uncategorizable symptoms of the syndrome, it looks like long covid is doomed to join the ranks of chronic autoimmune and central sensitization diseases that disproportionately affect women and are neglected by American health care.

The central sensitization syndromes include fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and they have symptoms like headache, brain fog and fatigue in common with long covid. Dr. Liisa Selin, a viral immunologist at the University of Massachusetts, noticed that long covid is virtually identical to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a poorly understood condition that causes debilitating fatigue.9

ME/CFS affects up to 2.5 million Americans, according to a report from the Institute of Medicine, but most of them have not been diagnosed. The illness may be more common among minority groups, though this is hard to measure because white people are more likely to seek care.10 The prevalence of ME/CFS is substantially higher in women than men, with estimates ranging from 75-85% of sufferers being women.11

Many researchers maintain that ME/CFS is, like long covid, the chronic aftermath of an acute disease, a viral infection. This is also true of multiple sclerosis, a debilitating neurodegenerative disease that affects four times as many women as men.12 Medicine has shrugged its shoulders about the cause of MS since it was first described in 1868, but recent studies have pointed to Epstein-Barr virus as the cause.13 Before research uncovered the etiology of diseases like ME/CFS and MS, they were talked about as just womanly troubles. Frayed nerves, psychological issues, a weak constitution. Hysteria by any other name.

I think another layer to the gendering of chronic versus acute illness is that traditional gender roles dictate that women are providers of care. Women care for the home, the children, the pets, the spouse and the elderly, and are expected to do so tenderly and indefatigably. So, before we had names and explanations for diseases like ME/CFS and MS, and even now that we do, they are spoken about in tones of accusation, the belief that a women being too ill to dispense care and instead asking for care is a failure, a betrayal of the nuclear family, an insult to the-way-things-should-be.

Unfortunately, these mass mommy issues—a repressed fear of abandonment, I dare say—are now baked into our health systems. The health care industry can’t accept that women are suffering more and certainly differently than men from a myriad of real diseases. Instead, they think women simply complain more, or suffer from hypochondria or stress or boredom or laziness more. Doctors still misattribute symptoms to psychology or hormones or even selfishness. As if being chronically ill is an intrinsic flaw of womanhood. Not treatable.

This is the legacy of hysteria, and it’s now impacting the care of 27 million more people. If chronic illness is coded female and therefore not taken seriously, and if long covid is adding millions to the ranks of the chronically ill every year, we’re about to face a decline in wellbeing the likes of which this country has never seen.

Declining wellbeing is something the U.S. government can write off as unquantifiable and therefore untreatable, but what about declining productivity? Beyond the gendered labor of caretaking, an increase in chronic illness means more “sick days” away from work, more people seeking employment that comes with health benefits, more people leaving physically exploitative jobs that shouldn’t exist in the first place. In Sick Woman Theory, Johanna Hedva argues that the sickness-versus-wellness binary is a capitalist construct:

The “well” person is the person well enough to go to work. The “sick” person is the one who can’t. What is so destructive about conceiving of wellness as the default, as the standard mode of existence, is that it invents illness as temporary. When being sick is an abhorrence to the norm, it allows us to conceive of care and support in the same way.14

Within this framework, acute illness is socially and politically tenable since it’s seen as a short-term problem. Like going to war! The threat emerges, the troops are deployed, the victory is secured, approval ratings soar. This is perhaps why, in the last century, we have adopted the language of disease to describe the invisible enemies of modernity: obesity is an epidemic, opioid addiction is an epidemic, misinformation is viral, certain political ideas are cancerous.

In Illness as a Metaphor, Susan Sontag notes that, "To describe a phenomenon as a cancer is an incitement to violence. The use of cancer in political discourse encourages fatalism and justifies ‘severe’ measures."15 The use of health-versus-wellness language in political discourse hinges on the belief that disease, like an enemy "other", can be conquered through an acute (masculine) display of force.

Under America’s particularly martial brand of capitalism, labor that exploits the body is like service to the state; labor should and must exploit the body to be considered essential. Since the mortification of the body is a characteristic of labor, a healthy body is required—a person being not-healthy and contributing to society at the same time is incomprehensible. This retrenches the gendering and racializing of illness because invisible forms of labor are already devalued.

For the benediction, a passage from Sick Woman Theory that reminds me of the first weeks of the pandemic when city streets were empty, offices were dark, factories were quiet, everyone was at home, anxious, struggling, adopting dogs and learning how to bake bread:

The most anti-capitalist protest is to care for another and to care for yourself. To take on the historically feminized and therefore invisible practice of nursing, nurturing, caring. To take seriously each other’s vulnerability and fragility and precarity, and to support it, honor it, empower it. To protect each other, to enact and practice community. A radical kinship, an interdependent sociality, a politics of care.

Because, once we are all ill and confined to the bed, sharing our stories of therapies and comforts, forming support groups, bearing witness to each other’s tales of trauma, prioritizing the care and love of our sick, pained, expensive, sensitive, fantastic bodies, and there is no one left to go to work, perhaps then, finally, capitalism will screech to its much-needed, long-overdue, and motherfucking glorious halt.

Harper Douglas, “Etymology of acute,” Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed August 27, 2022, https://www.etymonline.com/word/acute.

Harper Douglas, “Etymology of chronic,” Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed August 27, 2022, https://www.etymonline.com/word/chronic.

Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, et al. Sequelae in Adults at 6 Months After COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e210830. DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0830

Bull-Otterson L, Baca S, Saydah S, et al. Post–COVID Conditions Among Adult COVID-19 Survivors Aged 18–64 and ≥65 Years - United States, March 2020–November 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:713–717. DOI:10.15585/mmwr.mm7121e1

American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. “PASC Dashboard.” Accessed August 27, 2022. https://pascdashboard.aapmr.org/.

“A Clinical Case Definition of Post Covid-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus.” World Health Organization, October 6, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1.

Vahidy FS, Pan AP, Ahnstedt H, Munshi Y, Choi HA, et al. (2021) Sex differences in susceptibility, severity, and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019: Cross-sectional analysis from a diverse US metropolitan area. PLOS ONE 16(1): e0245556. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0245556

Sylvester SV, Rusu R, Chan B, Bellows M, O’Keefe C, et al. (2022) Sex differences in sequelae from COVID-19 infection and in long COVID syndrome: a review. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 38:8, 1391-1399. DOI: 10.1080/03007995.2022.2081454

McCluskey, Priyanka Dayal. “To Solve the Mystery of Long COVID, Researchers Look to an Older Disease.” WBUR News, August 8, 2022. https://www.wbur.org/news/2022/08/08/mystery-long-covid-chronic-fatigue-research.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2015. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. DOI:10.17226/19012.

Lim EJ, Ahn YC, Jang ES, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME). J Transl Med 18, 100 (2020). DOI:10.1186/s12967-020-02269-0

“Multiple Sclerosis: Why Are Women More at Risk?” Johns Hopkins Medicine. Johns Hopkins University, August 8, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/multiple-sclerosis-ms/multiple-sclerosis-why-are-women-more-at-risk#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20National%20Multiple,more%20women%20are%20developing%20it.

Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, Kuhle J, Mina MJ, et al. (2022). Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science (New York, N.Y.), 375(6578), 296–301. DOI:10.1126/science.abj8222

Hedva, Johanna. “Sick Woman Theory.” Accessed August 27, 2022. https://johannahedva.com/SickWomanTheory_Hedva_2020.pdf.

Sontag, Susan. Illness as a Metaphor: AIDS and Its Metaphors. Penguin, 1991.