“Godard said ironically that the epic was for Israelis and the documentary for Palestinians. […] To say that, in the dominant regime of representation, documentary is for the Palestinians is to say that they can only offer the bodies of their victims to the gaze of news cameras or to the compassionate gaze at their suffering. That is, the world is divided between those who can and those who cannot afford the luxury of playing with words and images.”

This quotation from a 2007 Artforum interview with French philosopher Jacques Rancière recently circulated on social media. Rancière’s comments focus on the art market and its subversion, but they found a new context amid Israel’s genocidal aggression against the people of Palestine.

I think of the notion of epic versus documentary every time a video taken by an IDF soldier surfaces on TikTok or Instagram: A soldier pretending he’s a realtor selling a destroyed Gaza home to a prospective settler. A soldier pretending he’s a teacher in an empty classroom, jokingly asking why all his students are late. A soldier pretending to sell his friends hookahs stolen in a raid, then smashing them on the ground. So much pretending. Epic is fiction, after all.

The cruel “play” in these videos reminds me of the Abu Ghraib photos. In comparison: Both parties are in the same bad place—a war zone, a prison—but the dominant party uses smiles and laughter to distance itself from the subjugated party. In contrast: The IDF videos aren’t secret snuff films but public social media posts. That they could be used as evidence of war crimes is of no concern, indicating the soldiers have been told or have assumed that they are above reproach. Though they dance around and mock like children, they imagine their make-believe is evidence of strength.

And, in a way, it is. In his 1984 article “Permission to narrate,” Edward Said writes that facts cannot speak for themselves but require a socially acceptable narrative to circulate them. He quotes historian Hayden White: “Narrative in general, from the folk tale to the novel, from annals to the fully realized ‘history,’ has to do with the topics of law, legality, legitimacy, or, more generally, authority.” Western superpowers have given the Zionist settler-colonial project the gift of legitimacy for 100 years, and this allows Israel to feel comfortably in command of the narrative, regardless of the facts, every time they launch a new wave of violence against Palestine.

On the other side, the designation of “terrorist” invalidates all claims to narrative. Everything inimical to western imperialism is terrorism, and terrorism is always illegal, illegitimate, indiscriminate. Everything inimical to western imperialism is anti-narrative. Palestinians are called terrorists to justify the slaughter of civilians and to erase Palestinian national identity and history.

-

On Feb. 11, 2024, while Palestinians in Rafah were busy surviving a siege by the IDF, Americans were sitting in front of their TVs with beer-glassy eyes and grease-shiny lips watching the Super Bowl. 100 million people watched a spot in which Zionist New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft talks about antisemitism. Kraft donates millions to AIPAC, attends fundraisers for the IDF and takes football players on “mission trips” to Israel.

American football fans were also targeted by a campaign from Israel’s National Public Diplomacy Directorate to “raise awareness” of the Israeli hostages who remain in Hamas captivity. The videos were disseminated via Paramount smart TVs, billboards, and sports and news websites. The “Bring All Dads Back Home” spot features home videos of Israeli fathers held by Hamas.

In “Permission to narrate,” Said recalls begging his friends and family in Lebanon to write down their experiences of Israel’s 1982 siege of Beirut: “It seemed crucial as a starting-point to furnish the world some narrative evidence, over and above atomized and reified TV clips, of what it was like to be at the receiving end of Israeli ‘anti-terrorism.’” Said recognized that Israel’s narrative will “win” if it is the only one visible to the rest of the world.

“Naturally, they were all far too busy surviving,” Said writes.

I can’t think of a piece of media more perfectly exemplary of contemporary epic than a Super Bowl spot. Cinematic editing, saccharine narration, a bit of slo-mo, maybe an aging celebrity, cultural references for easy digestion, millions of dollars sunk. Israel and its American allies can afford the luxury of playing with words and images.

-

Denying any people group the freedom to tell their own story by keeping them locked in a fight for survival opens the door to news and documentary film cameras, which invade and extract like any other force of imperialism, consuming brown bodies with a “compassionate” gaze.1

In an essay titled “Trauma Machine,” Elvia Wilk discusses how the rise of virtual reality enabled journalists and documentarians to turn images of war- or poverty-torn places into immersive experiences for western audiences. (Philanthropic VR projects putting people in the shoes of Syrian refugees were quite popular in the late 2010s.)

“There are two separate but twinned approaches to building interactive media with humanitarian aims. One stems from the belief that verisimilitude breeds empathy: walk a mile in her (literal) shoes without being told what to believe, and you’re more likely to form a personal connection. […] The second is the choreographed narrative approach, premised on the idea that embodied immersion allows more persuasive storytelling.”

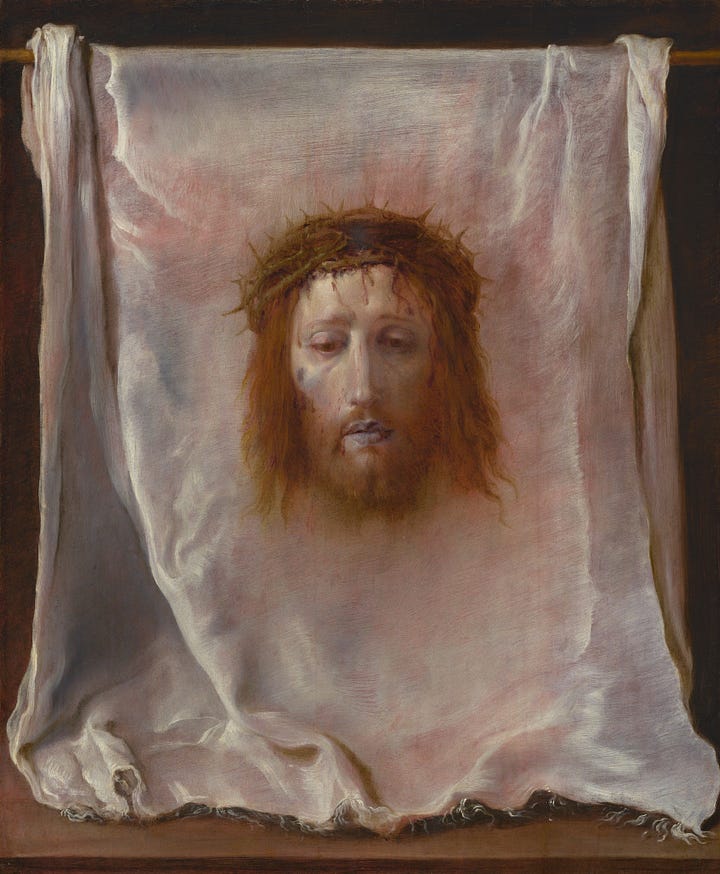

The word verisimilitude always makes me think of the Veil of Veronica. The name Veronica is a portmanteau of the Latin phrase vera icon, “true image.” Long story short, a gal named Veronica let the beleaguered Christ wipe his brow with her veil as he passed by on his way to get crucified. Miraculously, an image of his face was printed on the veil. The image became a relic, an acheiropoieton, a Greek term meaning “made without hand” that is used for Christian icons said to have come into existence without human intervention.

Relics are a funny business, but the story is important because it confirms that even before photography, even when “capturing” someone’s likeness was impossible without magic, representative images were highly potent, highly resonant vehicles for empathy. More important than the capture of Christ’s likeness was the capture of his pain.2 Veil of Veronica paintings, to me, project an aura of anxiety over the medium of painting, which necessarily fails to provide unmediated likenesses of anything. Images are only true when they’re untouched by human hands.

In today’s dominant regime of representation, both epic and documentary can be accused of favoring choreographed storytelling over verisimilitude. That is to say, the truth suffers when lots of money, private interests and geopolitics are involved. The only media that truly doesn’t tell you what to believe is media produced and consumed by equal means. Video shot on a smart phone and uploaded to social media is consumed via the same mechanism across the world, the only mediation being some translating, perhaps some blurring of gore.

-

One day my smart phone showed me a video of a young father holding up the limp body of his daughter, her footie pajamas covered with shooting stars and soaked in her blood. With flashing eyes he lifted her corpse to the ten iPhone cameras pointed at him, shouting in Arabic that all members of his family except for him had become martyrs while they slept. While he yelled in despair, a drop of saliva flew from his mouth toward the camera and I flinched.

-

Rancière implied that the commodifying gaze of the news camera and documentarian locks Palestinians into a passive objectivity, and appropriating the epic is an opportunity to snatch subjectivity back. I wonder, though, if joining Israelis in their make-believe would only adulterate the truth, which Palestinians have sharpened into a powerful weapon.

Rather, there is the third column, the one outside the dominant regime of representation, the representation that happens while Palestinians are fighting to survive.

Day after day, I watch Palestinian men and women lift the bodies of their children to camera lenses. In these invocations to look they usurp conventional narrative media and command hours and hours and hours of unmediated air time. Yes, Meta has done what it can to censure content about Palestine; Israel has done what it can to kill Palestinian journalists and photographers and filmmakers.

True images move people to take to the streets, to harass government leaders at restaurants, to clog congressional phone lines with calls. Palestinians like Bisan Owda and Motaz Azaiza3 are known to the world on a first-name basis; activists cite videos at marches and rallies, saying “I know we all saw the video of ___ this morning.” Images from social media are pulled up in media briefings, hearings and trials. There are iPhones and cameras lofted in the background of every video that flies from Palestine to the imperial core, a million eyes unblinking and multiplying, a million eyes resisting the tyranny of a single story.

Before Al Jazeera, the first independent news channel in the Arab world, launched in Qatar in 1996, western news corporations like the BBC operated bureaus in the Middle East. Colonizers hate independent media, and they certainly hated that Al Jazeera (and the internet) were suddenly telling the world the Arab side of the story: Al Jazeera’s Kabul bureau was bombed by the U.S. military in 2001 and its Baghdad bureau was bombed by the U.S. military in 2003. Many of the internationally beloved journalists targeted by Israel for their reporting from Gaza work for Al Jazeera, which opened a Palestine bureau in 2000.

The suffering of Christ is a culty thing that has made for some very fun art and ephemera. Holy effluvia—tears and blood—were represented in medieval devotional texts and readers would rub and kiss them to feel more embodied in their empathic connection to Christ. There are examples of devotional texts with “life-sized” representations of Christ’s side wound that featured an actual slit in the paper that readers would stick their fingers through. Whew.

Excellent; definitely continuing the revising of my view on this situation. "...commodifying gaze" "a million eyes unblinking and multiplying, a million eyes resisting the tyranny of a single story."

Well done.