The witch is my favorite part of Halloween. She’s my favorite trope in horror because she can be sassy or charming or deeply terrifying, depending on what she’s wearing and what she wants. She lends nuance to any media she appears in because she can’t be separated from her history. She played a significant role in the making of American culture, in civilization itself, so every time her image is deployed, it calls up an ancient (and gendered) discourse.

For the October issue of Medusa’s Body (I think Hélène Cixous would agree with me when I say: who was Medusa but a witch without a broom?) I thought I’d get festive and consider how the witch is a strongly expressed grotesque, especially when she laughs.

Generally speaking, witches were/are people who use magic spells and contact spirits. They have existed in many forms on many continents across many millennia. For my purposes, I’m focusing on the witch in Christian-dominated cultures, namely North America in the past few centuries. In this context, witches were thought to be pagans, heretics and mistresses of the devil, though many were simply practitioners of folk medicine whose skills were misunderstood.

One of the earliest historical records of a witch is in the Bible in 1 Samuel, thought to be written between 931 B.C. and 721 B.C. The story tells of King Saul seeking the Witch of Endor to summon the dead prophet Samuel’s spirit. It didn’t work out well for Saul, so the obvious moral of the story is “witches are bad, go to God for your miracle needs instead.”

A handful of other Old Testament verses condemn witchcraft, divination, chanting and contacting the dead. Christians used these verses to justify the hunting, torturing and killing of thousands of “witches,” mostly women and the poor. Between the years 1500 and 1660, up to 80,000 suspected witches were murdered in Europe.

The publication of the Malleus Maleficarum, usually translated as the Hammer of Witches, helped normalize witch hunting by conflating sorcery with heresy and recommending that secular courts prosecute it as a crime. Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer published the book in Germany in 1486. It’s basically a guide on how to identify, interrogate and execute witches, and for more than 100 years, the book sold more copies than any other in Europe except the Bible.

Witch hysteria slowed in Europe around the turn of the 18th century but grew in the “New World,” which was in need of scapegoats amidst wars with the French and British, a smallpox epidemic and ongoing conflict with the original peoples whose land was being occupied. Within a century, witch hunts were common and most of the accused were single women, widows and other women on the margins of society.

If you’ve been reading Medusa’s Body for any length of time, you won’t be surprised to learn that the gendering of the witch is what is of most interest to me here. Gender is one of the many binary oppositions that mankind has invented in order to have stable structures on which to build civilization. Having two opposite realms that are clearly defined and mutually exclusive leaves no room for the chaos of ambiguity, of multiplicity, of change.

The Christian binary of good versus evil/righteousness versus sin/God versus devil poses a bit of a theory problem since evil can be seen proliferating on earth despite the omnipotence of God. Understanding witches as human agents of the devil employed to do his bidding on earth, and understanding women as naturally susceptible to the devil, provided a tidy restoration of order—relief from chaos.

“All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable,” says the Malleus.

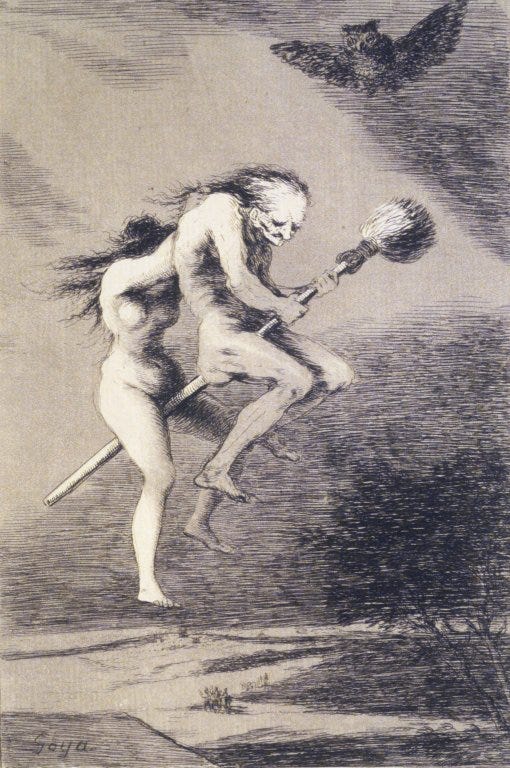

The gender binary was one that both the Church and the law called on often to justify moral beliefs. Feminine sexuality was seen as a force of chaos that had to be contained, and the Malleus put this into legally actionable terms (legal versus illegal being another familiar binary). According to the Malleus, once a witch accepted the devil, she immediately acquired the ability to fly from place to place and the regular attentions of a demon lover. The demon lover thing is like, hilarious, but the flying is my favorite part—enter the broomstick!

The broomstick is perhaps the most delightful way witchcraft was linked to feminine sexuality. The earliest known image of witches on brooms dates to 1451, when two illustrations appeared in the French poet Martin Le Franc’s Le Champion des Dames (The Defender of Ladies). In the drawings, two very normal-looking women soar through the air on broomsticks.

The broom is a symbol of feminine labor and domesticity (the same can be said of the bubbling cauldron), but it’s also a phallic shape, making the broom between the legs a very housewives-gone-wild image. Pagan rituals and folk fertility ceremonies before the 15th century had involved phallic forms, so the shape of the broomstick between a woman’s legs packed a one-two punch of both sexual and spiritual deviance.

In the 15th century, a writer named Jordanes de Bergamo said, “The vulgar believe, and the witches confess, that on certain days or nights they anoint a staff and ride on it to the appointed place or anoint themselves under the arms and in other hairy places.” Hallucinogenic drugs of the time such as ergot fungi, which had effects similar to LSD, could be dangerous to ingest, so they were applied topically to mucous membranes, which are found in “hairy places” including the armpits, anus and vagina. (Note to self: watch Portrait of a Lady on Fire again.) Johann Weyer, in his 1563 Praestigiis Daemonum, said other hallucinogenic plants including henbane, deadly nightshade and mandrake were principal ingredients in any witch’s “flying ointment.”

Antoine Rose, who was accused of witchcraft in France in 1477, confessed that the devil gave her flying potions. She said she would “smear the ointment on the stick, put it between her legs and say ‘Go, in the name of the Devil, go!’”

Am I saying that all witchcraft was just women doing drugs and masturbating? No, but there is something delightful in the innocuousness of this particular bit of witch history. Men would really rather accuse women of causing illnesses, natural disasters and crop failures in the name of the devil than accept that they want to have fun sometimes.

Feminine sexuality existing outside of the confines of the marriage bed implies that femininity is more than the object and foil of male sexuality. The lore around witches involves women experiencing pleasure (via drugs, makeshift dildos, sneaking out of the house to party with other women in the woods) and enacting change (healing, making potions, bringing dead things to life) in ways that transgress the phallocentric gender binary that figures woman as desirable to man because she completes him, defines him by contrast as his Other.

“What else is a woman but a foe to friendship, a necessary evil, a natural temptation,” says the Malleus. “And what, then is to be thought of those witches who in this way sometimes collect male organs in great numbers?” Feminine sexuality liberated from its normative container is devouring, chaotic, threatening. The witch does not complete man, rather, she consumes him.

Feminine power within society was/is subsumed within a discourse of gender and sexuality, meaning that any disordering manifestation of women’s power, influence, or behavior must be understood in terms of sexual perversity—insatiable, carnal lust. The witch who exists outside of the gender binary destabilizes it, which calls into question the stability of all binaries. A punishable offense indeed.

I hear a measure of this supposed carnal lust in the inclusion of laughter in the witch image. You know what I’m talking about—that screechy, crackling laughter that made you shudder as a child but is now relegated to campy haunted houses and low-budget horror movies. There’s a lot to be said about villainous laughter—how it invokes insanity, sadism, an abjecting inversion of norms—but I’m not convinced that the witch is a villain, so here I’m going to focus on the grotesqueness of feminine laughter in general.

Mikhail Bakhtin, who developed a theory of the grotesque body through a close reading of medieval folk culture as represented in the fiction of Rabelais, devoted a whole chapter of his analysis to laughter. In Rabelais and His World, Bakhtin characterizes the “popular-festive laughter” found in Rabelais as a distinctly counter-institutional, communal and bodily experience.

To understand the festive laughter found in Rabelais, imagine the laughter that ensues when you’re in a haunted house and a jump scare makes your friend trip and fall into a guy dressed up as a zombie butcher. You and your friends are laughing so hard you’re clutching your stomachs, and after a few minutes the laughter quiets enough for your friend to say “I think I peed a little bit,” and then it starts back up again. For the rest of the night, you can’t look at your friends in the eye without the whole group dissolving into giggles.

This laughter is not villainous or mocking but pure, delightful—it is characterized by universalism, freedom, a relation to the “people’s unofficial truth,” per Bakhtin. It’s marked by togetherness and a sense of embodiment. Bakhtin says this laugher represents “victory over fear” and “uncrowning and renewal, a gay transformation”—it “create[s] no dogmas.”

Laughter is closely connected to the grotesque body, which is defined by its emphasis on the lower stratum, the realm where the body enacts both degradation and renewal through actions like sex and eating, pregnancy and defecation. Both the grotesque body and its laughter emphasize a shared experience outside the privacy of the home and domestic life.

In The Laughter of Sarah by Catherine Conybeare, a brilliant book about why Sarah (wife of Abraham in the Bible) laughs and what it means, the author cites Bakhtin in her search for a theory of feminine delight. Bakhtin’s association of laughter with the bodily lower stratum, according to Conybeare, allows him to “set down in writing an agglomeration of properties of laughter that we feel instinctively to be apt, but that are hard to ground in the conventions of academic discourse and attribution.” In other words, much critical-theory discourse was written in the 20th century about laughter, but none had the courage to admit that the body produces hilarity on its own.

Bakhtin says woman is “essentially related to the material bodily lower stratum; she is the incarnation of this stratum that degrades and regenerates simultaneously.” This must be taken with a grain of salt since we want to avoid claiming an essential connection between womanhood and the maternal function. Rather, we can consider how the long history of conflating womanhood with uterus-having has led to an understanding of women as containing generative power in their bodies.

“She is ambivalent,” Bakhtin says, ambivalence being a central quality of the grotesque. “She debases, brings down to earth, lends a bodily substance to things, and destroys; but, first of all, she is the principle that gives birth.” At this bodily point, the lofty is made concrete (after all, a baby’s tissues are made out of proteins that came from the fried chicken sandwich its creator ate for lunch), lending it a ripeness for the universal, unadulterated laughter of delight that Bakhtin describes.

I believe that woman’s laughter being twisted into a villainous signifier in the case of the witch tracks with the twisting of the healer or wise-community-elder into something devilish. It’s the twisting of something familiar into something dangerous that abjects, creates horror: the witch’s materials can be found in every kitchen, the desire for communion, flight, orgasmic joy in every body.

In the Malleus, witches are divided into three classes: those who only cause harm, those who heal as well as harm, and those who heal but cannot cause injuries. She destroys but also renews. This ambiguity was cleansed, put back into order, through the grotesque becoming laden with moral, ethical, political and religious implications throughout time. Conflating the ambiguity of the grotesque with sexual perversity, heresy, crime, evil, etcetera, serves to crush the chaotic multiplicity of nature.

Bakhtin warns that when the grotesque is used to illustrate an abstract idea such as moral virtue or sin, its nature is inevitably distorted:

“The essence of the grotesque is precisely to present a contradictory and double-faced fullness of life. Negation and destruction (death of the old) are included as an essential phase, inseparable from affirmation, from the birth of something new and better. The very material bodily lower stratum of the grotesque image (food, wine, the genital force, the organs of the body) bears a deeply positive character. This principle is victorious, for the final result is always abundance, increase. The abstract idea […] transforms the center of gravity [of the grotesque image] to a ‘moral’ meaning.

The laughter of the witch, perhaps because it represented unacceptable feminine delights—the delight of freedom, the delight of power, the delight of togetherness, the delight of sexual gratification—became a signifier of her perversity.

The witch, of course, persists. “The grotesque images selected to serve an abstract idea are still too powerful; they preserve their nature and pursue their own logic, independently from the author’s intentions, and sometimes contrary to them,” Bakhtin writes. I assume the manic hunt for witches as North America was colonized had at least something to do with the diverting nature of fantasy, the intrigue of feminine sexuality as an incomprehensible continent. This intrigue continues to express itself in popular media, feminist thought, high art and everything in between.

For the benediction, a reminder from Cixous’ “The Laugh of the Medusa:” “You only have to look at the Medusa straight on to see her. And she’s not deadly. She’s beautiful and she’s laughing.”

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

Broedel, Hans. The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft. Manchester University Press, 2013.

Cixous, Hélène. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Translated by Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1, no. 4 (1976): 875–93.

Conybeare, Catherine. The Laughter of Sarah: Biblical Exegesis, Feminist Theory, and the Laughter of Delight. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

History.com Editors. “History of Witches.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, September 12, 2017. https://www.history.com/topics/folklore/history-of-witches.

Meier, Allison. “The First Known Depiction of a Witch on a Broomstick.” Hyperallergic, October 27, 2021. https://hyperallergic.com/332222/first-known-depiction-witch-broomstick/.

Thuras, Dylan. “Sex, Drugs, and Broomsticks: The Origins of the Iconic Witch.” Atlas Obscura. Atlas Obscura, July 6, 2021. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/why-do-witches-ride-brooms.