The Grotesque and the Female Body

"Degradation digs a bodily grave for a new birth; it has not only a destructive, negative aspect, but also a regenerating one.”

I’m beginning a series of essays on the grotesque.

These essays will explore the grotesque as a gendered concept with deep roots in literature, art, religion, and culture at large. I will look through this concept at various gender-related conflicts in Western culture, hoping to both demystify and defamiliarize.

The grotesque is an art historical term that has often crossed into literature. I became interested in it while reading Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, in which a young woman experiences a series of mental and physical traumas that disfigure her. This disfigurement takes place during the 1950’s, an era with heavy expectations for women—beauty, chastity, politeness, quietness, which add up to monumentality. I believe the raw, bodily images of Plath’s heroine can be defined as grotesque, which suggests a meaningful contrast between the monumental female body and the grotesque female body.

Before I go into more detail, we need to go back in time to locate a workable definition of the grotesque. The word is currently understood as synonymous with disgusting, horrifying, monstrous, hideous. Like most words, however, “grotesque” has been simmering on low for hundreds of years, reducing. Etymologically, the word comes from “grotto,” which, very-long-story-short, refers to the 15th-century excavation of interior rooms of an Ancient Roman palace; the rooms were decorated with wall paintings of people and animals fused with plants—think animals with stems for legs and flowers with human faces. The paintings defied the natural order, played with it, which blew everyone’s mind.

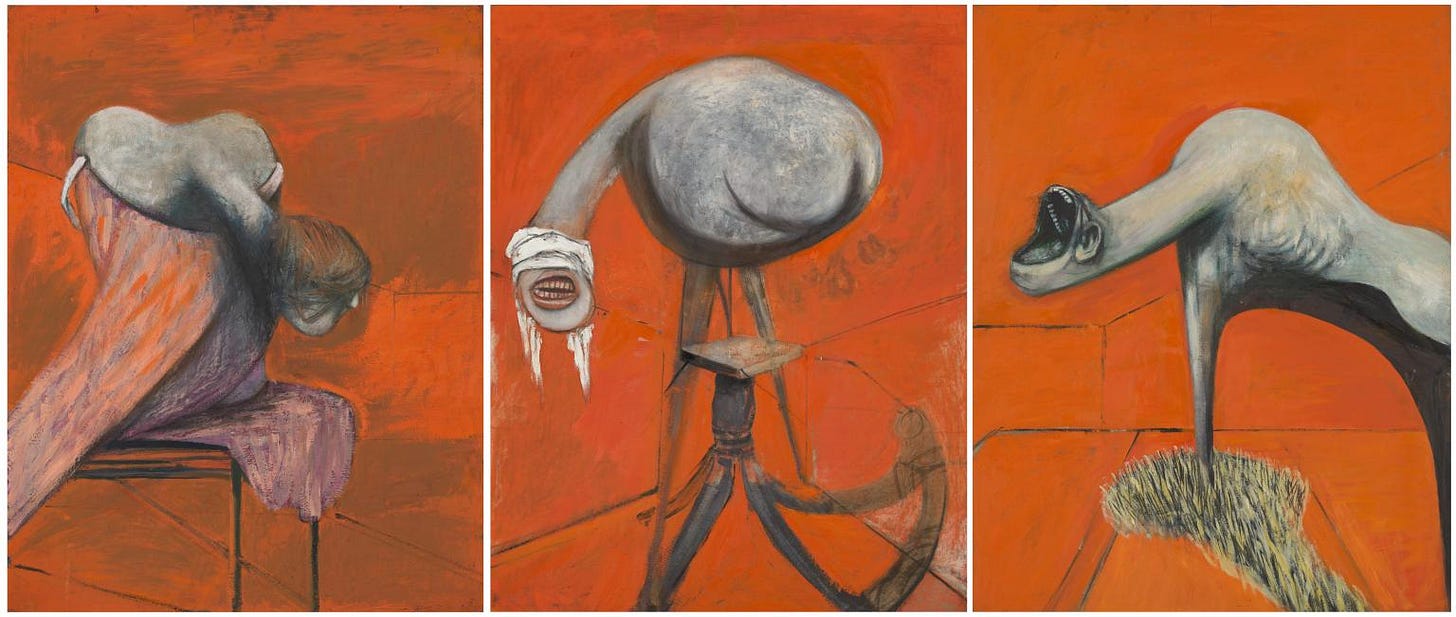

So, the root of the grotesque is in the playful transgressing of nature’s boundaries, the questioning of nature’s laws. Where does the body end and nature begin? Where does human end and animal begin? This sense of play was a lightning rod in the European artistic imagination, and the influence of the “original” grotesque has been far-reaching.

In his 1965 book Rabelais and his World, literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin explores the culture of the Middle Ages as depicted by the French Renaissance writer Francois Rabelais. Rabelais’ novel Gargantua and Pantagruel is full of vivid images of social life in the Middle Ages, and from them Bakhtin extracts the idea of the grotesque body, which expressed itself freely in medieval public settings such as the marketplace or carnival.

Per Bakhtin’s definition, the grotesque body is open, porous, bulging, exchanging with other bodies and the world around it. Think of the mouth: eating, drinking, vomiting, swapping spit with your high school crush behind the funnel cake stand at the county fair. Think of the reproductive organs: sex, menstruation, pregnancy, squeezing a wriggling mass a flesh out of your own body in the back of taxi while screaming bloody murder. The grotesque emphasizes the “lower stratum” of the body where things go in and out, where that invisible boundary we draw between ourselves and the outside world is transgressed. Grotesque figures were often depicted in art with protruding body parts such as big ears or noses in order to represent this transgression.

The actions that define the grotesque body are normal human processes, yet they’re “gross” and impolite to talk about. Why? Centuries ago, the primacy of public living gave way to a desire for privacy, personal space, and hygiene, which meant the grotesque body stopped being accepted as a normal, healthy part of social life. The grotesque remained very much alive in the Western imagination and in Western culture, but the attitude of grotesque images became more negative as the body became less free to express itself.

The female body, well before the 50’s and certainly ever since, is seen as something that should be monumental and closed. It should have clear, porcelain skin, a closed mouth, and closed legs. The grotesque processes of women’s “lower stratum” happen behind closed doors and are never talked about. Women defecate? Women enjoy sex?! Unspeakable! Western culture refuses to accept such truths, and as a result, monumentality is policed, reproductive health care is inaccessible to many, and accurate information about menstruation, sex, and childbirth is withheld.

Far from monumental, Plath’s heroine Esther Greenwood is seen vomiting her guts out following a pinky-up luncheon at a women’s magazine. A man assaults her and she smears her own blood on her face, letting it turn brown and crusty. She desires sex, seeks it out, has it, hemorrhages and feels her shoes fill up with blood. Plath portrays the grotesqueness of one young woman’s lived experiences in a way that I believe was unprecedented. Women’s media and the social norms it extolled breath down the neck of the book, and I think Plath’s sometimes difficult-to-stomach portrayal of the suffering of young women under 1950’s patriarchy was an act of resistance.

The image Bakhtin calls upon to represent the grotesque body is a laughing, pregnant hag. I’ll repeat: a senile old woman, pregnant, and laughing. This “unnatural” image combines life and death in a dynamic way, just as the lower stratum of the human body produces both degrading material and new life. Bakhtin wrote that there is “nothing completed, nothing calm and stable in the bodies of these old hags.” They contain the “twofold contradictory process” of life in their own bodies. What power!

I could write 100,000 words about the hags’ laughter, but suffice it to say this: I read their laughter as a big Fuck You to the natural order (patriarchy’s understanding and enforcing of it, rather) that seeks to limit their bodies’ power to decay and create at the same time. The instability of their bodies is terrifying to the enforcers, and they laugh with pleasure.

In The Bell Jar, Esther attempts suicide by taking pills and burying herself in a crawl space in her basement. She is later unearthed, excavated, resurrected but changed. When she awakens in a hospital bed, she doesn’t recognize herself: “One side of the person’s face was purple, and bulged out in a shapeless way, […] The most startling thing about the face was its supernatural conglomeration of bright colors. I smiled.” She is discolored, bulging, grotesque, and she laughs in defiance of the monumental.

Throughout the novel, Esther brushes with death, injury, illness, blood, and yet she is always rising again. At the end of the story, despite the traumatic summer that nearly kills her, Esther begins writing herself into a novel. Creating and re-creating herself. Bakhtin said “degradation digs a bodily grave for a new birth; it has not only a destructive, negative aspect, but also a regenerating one.”

This creative energy found within the grotesque is important and exciting to me because Western culture tends to associate rebirth only with Christianity. Instead of reserving the power of resurrection for the ubiquitous Christ Figure, grotesque theory re-situates this dynamism in the female body. What power.

I’ve only scratched the surface of how the grotesque can inform an analysis of gender, sexuality, feminism, patriarchy, and so on.

Here are some of the concepts I’ve touched on but will explore in more detail in upcoming essays:

How and why patriarchy forces monumentality on female bodies, and how it hurts us

How images of the monumental female body are weaponized by fascism

How the conflict between the monumental and grotesque is at play in the politicization of abortion, contraception, sexual assault and criminal justice

How artists, authors and poets resist the oppressive image of the monumental body by playing with and in the grotesque

Stay tuned.

This essay was originally published in July 2019 on my personal blog.