Control is a big thing for me. I want everything to bend to my will. But life doesn’t work like that and the things that I can reliably control are very few. The groceries I get, my to-do list for the day, everything else is chaos. I’ve built myself a little raft of controllable things and most of them relate to my body. Control has narrowed into self-control — I’m the only one bending to my will.

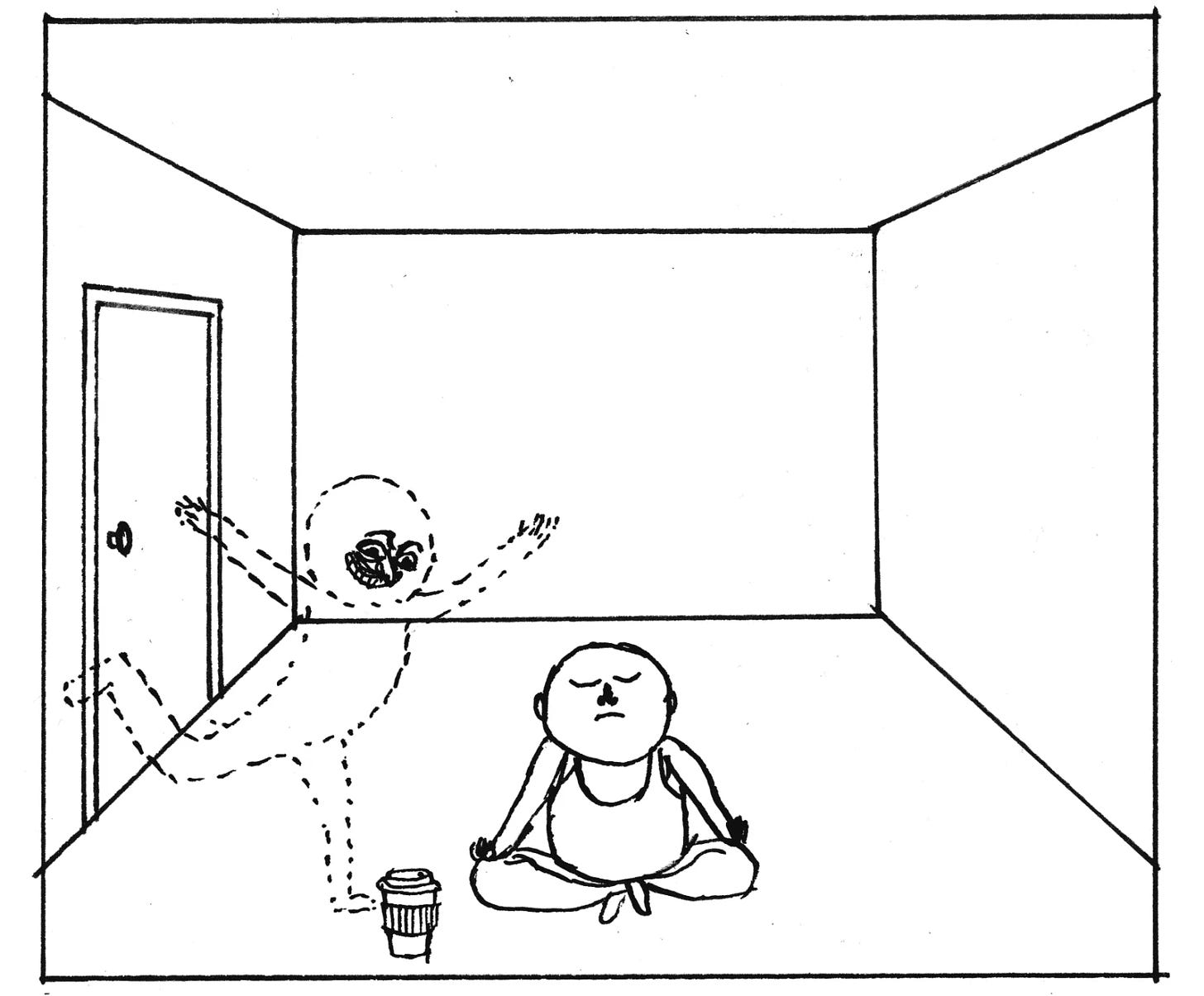

Self-control is a balm for the anxiety of the unknown: I can’t promise myself a stable future, a safe world to raise children and grow old in, but I can labor to contain the chaos within myself. Though it’s mortifying, there must be holiness in that work of self-containment. To put it plainly, manipulating myself makes me feel powerful and safe. A little autocracy of one. I control the news, I’ve got secure borders.

I came to the idea of the grotesque versus the monumental when I realized that it’s not just mental illness that has me thinking this way (mental illness is definitely part of it though lol). It’s not just neurosis that has caused me to be so devoted to self-mastery, so enthusiastic about self-surveillance. I am being discipled by external structures that benefit from my being more concerned with my body than anything else. This preoccupation — with the size and shape of my body, the status of my “health” and “fitness,” the habits and routines of my days — keeps me isolated, it keeps me subservient to capitalism, and it ensures that I’m too insecure to make claims to power.

The monumental body is docile and beautiful, but constrained, while the grotesque body is a body in community that lets loose its transgressive power. The all-consuming project of controlling the grotesque self abjects. The body, mind and spirit are wilderness, and they resist conquest right until they’re ruined by it. Resistance creates resentment, and resentment leads to alienation from the embodied truth of the self.

But, but, but, the seduction of self-optimization is everywhere. It’s not just me, it’s not just you. I’ve written previously about how “the new technologies of fitness function as the beauty myth’s discipline in disguise,” so I won’t get into the Foucault of it all, but suffice it to say we’re being sold a bill of goods that encourages us to internalize the discipline of patriarchy, capitalism, white supremacy, all of the superstructures that require docile subjects.

When I say docile in this context, I’m thinking of our longing to conform, to wear the same clothes and have the same body shape as a popular girl on the internet. I’m thinking of our longing for perfection on a scale so granular that we have to enlist outside help to define it: deep sleep, resting heart rate, metabolic efficiency.

We’re taught to believe that happiness or peace or who even knows what the goal is can be ours if we make the right purchases and cultivate the right habits. If we labor to mold ourselves into an external image of beauty/health. We don’t feel docile because our self-optimization projects are so high-effort and high-intensity, but our self-facing gaze implies a blind eye to the outside world.

When I wrote on the topic of body projects last year, I was thinking about smart-watches and fitness apps and diet culture things like that. Since then, the technologies of self-policing have only gotten deeper, more discreet, more cellular:

The Oura Ring is meant to be worn constantly for constant self-monitoring. Here’s the copy featured prominently on the website: “Feel good.

Look good. Feel your best with the Oura Membership, powered by the Oura Ring — the most advanced, accurate smart ring available. Monitor your sleep, activity levels, temperature trends, stress, heart rate, and more. Whether you’re focusing on your fitness or managing your stress, Oura helps you take control of your health — in style.”Interested in sleep surveillance but don’t want to wear a ring to bed? The Amazon Halo Rise bedside sleep tracker sits on your bedside and watches you dream. It uses “low-energy sensor technology to track body movement and breathing. Also measures room temperature, humidity and light.”

The Upright Go 2 device adheres to your back and vibrates when you slouch, reminding you to stand up straight. The device connects to an app to collect data on your slouching, allowing you to track your slouching progress. A user testimonial on the website reads, “I barely noticed the device was there except for when it vibrated.”

The Lumen metabolism tracker is a breathalyzer device marketed as “the first device to hack your metabolism.” It measures the CO2 in your breath to tell you what kind of energy you’re burning in that moment — this information supposedly helps the user “enhance fat burn, lose weight & boost energy naturally.” The website says: “Once available only to top athletes, in hospitals and clinics, metabolic testing is now available to everyone.”

The implications of this technological-self-monitoring gaze, this auto-panopticon, are various:

The language of self-optimization makes already healthy people think they need to be more healthy. This makes health and fitness, by extension beauty and thinness, into a never-ending project, a state of being that gets farther away the closer you get to it.

There’s a sound bite from American Psycho trending on TikTok right now, the scene where Patrick Bateman says “I’m on a diet” and when Jean asks why, since he already looks so fit, Bateman says, “Well, you can always be thinner, look better.” Disturbingly, yet unsurprisingly, TikTokers are using this sound to show off successful weight loss/fitness transformations.

The language of self-optimization also harms people with chronic illnesses and disabilities. These devices fuel ableism, agism and fatphobia since the messaging around them implies that any body that’s not at peak performance and peak fitness needs fixing. And that fixing one’s body is one’s own responsibility: you should be able to alter your body composition and mental wellbeing through sheer force of will. This empowers the medical industry (and the psychiatry/normative mental health industry!) to police norms as if they’re containing epidemic diseases.

There is a health gap analogous to the wealth gap in the U.S.: as rich people get richer, healthy people get healthier, while the “middle class” disappears. It is becoming harder for average people to access average health services, and people who don’t fit the norm of “healthy” are devalued by our capitalist-materialist society that equates health with productive value with moral value with beauty with humanity. Meanwhile, the ruling class is worrying about their posture and the light pollution in their bedroom.

Self-monitoring technologies veil the beauty imperative in wellness messaging so that young women in the ~age of self-care~ will still buy into it. Millennials and Zoomers are very vocal about social justice issues, mental health, eating disorders, trauma, body image and identity politics, which should have diet culture running scared. Instead, diet culture has rebranded as self-care and wellness: influencers are careful to qualify that their oil-free plant-based “what I eat in a day” videos are “realistic” and free of restriction; they promise that they start their mornings with celery juice because it makes them feel good.

Self-monitoring technologies encourage a strange enmeshment with data, which alienates us from our physical bodies. Yes, medicine relies on data to understand health and disease and that’s good, but translating our everyday lives into metrics and trends creates a layer of artifice over us that we perceive as truth but is merely interpretation. The truth is grotesque and the interpretation is monumental, it’s sanitized and detached and framed in a specific way to convey a specific narrative. Trying to know ourselves via numbers is futile. The grotesque body integrates chaos, it resists logic, it certainly resists control. Fighting the body makes us feel split in two.

The exploding market for self-monitoring devices and apps shows that we’re going numb to the feeling of being watched. We buy these technologies because they tempt us with control, omnipotence over our bodies and lives: “take control of your health — in style.” We think it’s us doing the controlling, the monitoring, the watching. At the risk of sounding like a conspiracy theorist, I think our willingness to consent to surveillance is extremely dangerous. The private companies behind our fitness apps and devices have financial and political ties that lead to some suspicion from consumers but mostly just shrugging. The shrugging is a bad sign.

If “taking control” of ourselves is necessary of an optimal life, we will of course see a lack of control as synonymous with failure. Our culture uses the phrase “letting yourself go” in a derogatory and threatening way to talk about weight gain or lapses in beauty/fitness routines. The phrase was and is still terrifying to me because it sounds so existential, so open-ended. Go where?! Like if I stop dieting and allow whatever weight gain may come, I’ll drop off the face of the planet.

A lack of control implies a loss of beauty, sexual attractiveness, moral standing, virtue, all of these signifying a loss of value in society. This belief that control is central to selfhood is a product of centuries of discipline that made people into docile laborers and state subjects, though in our 21st century ~democracy~ that values ~freedom~ this discipline has been internalized. Our obedience is now policed by our friends, sisters and mothers, the media we choose to consume, the products we choose to buy.

For the benediction, a few excerpts from Sinister Wisdom 36: Surviving Psychiatric Assault & Creating Emotional Well-Being in Our Communities. Sinister Wisdom is a multicultural lesbian literary and art journal that has been publishing since 1976 — its full archive is available here. Editor and publisher Elana Dykewomon’s introduction to the Winter 1988/89 issue on psychiatric abuse has been quoted a million times over (if you were ever on tumblr you’ll recognize the quote right away.) But the rest of the introduction, and that issue of the journal, contains an amazing discussion on control, losing control, and the punishments women endure once they’re labeled “out of control.”

Womyn are encouraged, more and more, to seek “professional help” in order not to go crazy. Why the idea of “losing control” is threatening deserves a paper itself - groups who have very little power are afraid of losing what privileges they have, police each other to avoid retaliation from their enemies, retreat from a world clearly out of control by projecting the perfect self-image. Still, almost every womon I have ever met has a secret belief that she is just on the edge of madness, that there is some deep, crazy part within her, that she must be on guard constantly against "losing control" - of her temper, of her appetite, of her sexuality, of her feelings, of her ambition, of her secret fantasies, of her mind. […]

When we hate ourselves we think we should be cut, mutilated, starved. We no longer seem to see these as social patterns but as individual problems. What has stopped us in our tracks and has us wandering from therapist to guru to astrologers and back, caught up in perpetually getting our shit together? […]

More dream circles, more picnics. More talking, more writing, more issues like this one, where we can show each other not only our center, but our farthest edge.

I keep thinking about how control gives me this false sense of safety and security. But rather, I'm just holding onto something so tightly that I am unable to see anything else. Unable to WANT anything else. As if, control is equivalent to consistency. But I think in order for consistency in our lives to be authentic to who we are and the selves continue evolving into, there must be release of what does not work. When we surrender and allow ourselves space, there's finally room to breathe. After reading this, I feel renewed to consider what is possible when we lean into consistent breath flowing freely.